The Digitization of Hindu Spiritual Guidance: A Comparative Study of Online and Real-Life Gurus (by Anonymous)

The following is an insightful research paper on the modernization of religious practice, providing great insight into what the future of theology may look like through the lens of Hinduism.

The Digitization of Hindu Spiritual Guidance:

A Comparative Study of Online and Real-Life Gurus

0. Introduction

In the Hindu religion, the Guru serves as a spiritual guide for followers. This research paper explores the influence of the digital age on Hindu religious counseling. Specifically, the current difference between modern (online) and traditional Gurus.

1.0 Background

Hinduism, considered by many the oldest religion in the world, dates back over 4,000 years. Many scholars argue that the polytheistic religion started in the Indus River Valley, one of the five major cultural hearths of the world, somewhere between 2300 BC and 1500 BC. However, many Hindus believe that their religion is even older, as argued by Mrs. Anupanum, a local Hinduism and Hindi teacher in the UAE.

The original Hindu teachings were encapsulated by the Vedas, a collection of four scriptures (the Rigveda, Samaveda, Yajurveda, and Atharvaveda) dated by most scholars to be written around 1500 - 1200 BC. These sacred texts were passed down orally through multiple generations before finally being put to paper. Originally meaning “knowledge” in Sanskrit, the language it was written in, the Vedas contained hymns, philosophical discussions, and praise for a pantheon of Gods. In addition to that, the texts emphasized the importance of Gurus, people who are seen as spiritual guides and teachers. Following the Vedas, many other important religious scriptures and epics such as the Bhagavad Gita, Ramayana, and Mahabharata were put in black and white, expanding the breadth of the Hindu faith.

An extract from the Rig-Veda, written in Sanskrit (early 19th century CE)

For Hindus, more than most other religions, one’s own religious beliefs and version of the truth is heavily influenced by where one was born, what scriptures one identifies with and what Gods they predominantly pray to. These differences are by nature of Hinduism’s polytheistic system which contains thousands of deities and demi-Gods.

Nevertheless, the core beliefs of the religion stay relatively the same among all its followers: That is, the cycle of reincarnation and the eventual return to God. To explain more thoroughly, central to Hindu religious philosophy is the Sanskrit term Dharma. Essentially, Dharma refers to a set of religious duties that people can follow to live better and more meaningful lives; this ethical code attaches great importance to values such as truth, right conduct, love, peace and non-violence. Moreover, each person’s Dharmic duties are individualized, with the path for every living soul being different.

Your accordance to your Dharma is then used to help decide your next life in the reincarnation cycle. This process represents the important Hindu principle of Karma. Essentially, if you follow your duties in this life, God will reward correspondingly in your next life and vice versa. This would come in the form of you being born into a higher or lower class family, or as a higher or lower species. This cycle of rebirth, known as Samsara in Sanskrit, finally ends with the eventual re-joining with God, known as Moksha.

The return to God is a return to Brahman, the supreme being in the Hindu faith. Interestingly, Hindu deities are different manifestations of the Brahman. This is considering the fact that in its raw form Brahman has no shape or form, making it harder for humans to understand. Therefore, through distinct forms of Hindu idols, Hindus can learn about pieces of Brahman in a way that they can understand. For example, the God Shiva is depicted as holding a trident, which symbolizes destruction in the Hindu faith and thereby in Brahman. For that reason, the view that Hinduism is a polytheistic religion is not a complete one, owing to the fact that in reality it is based in one supreme being.

Now the basics of Hindu thought are clear, it begs the question of the Guru's role in the grand scheme of the religion.

"Guru is Shiva sans his three eyes,

Vishnu sans his four arms

Brahma sans his four heads.

He is parama Shiva himself in human form"

~ Brahmanda Purana

The Puranas are a number of Hindu texts that primarily focus on Hindu lore and legends. Literally translating to old/ancient, these scriptures date back to the 3rd century AD. The excerpt above, from one of the oldest Puranas, perfectly illustrates how the Guru is seen in Hindu religious philosophy. It compares the Guru to a God, saying that they are God in human form. In other words, Hinduism sees the Guru being as essential as the many Gods. The significance of the Guru is in view of the fact that they are a mentor that comes to you in the flesh. Just as God helps you from the heavens, a Guru imparts knowledge on you to live a better life. To put it simply, a Guru is a spiritual teacher, a guide.

The word Guru, along with other terms derived from Hindu tradition, has since expanded and is now used more loosely in everyday language. For example, someone would say that their life coach is their Guru, and a Tony Robinson quote is their daily mantra.

As technology continues to grow through the centuries, human perspectives have changed, the flow of information has increased, and the number of Hindu followers worldwide has grown. Consequently, the role of Gurus has expanded and changed. Now more than ever, people now have the ability to tap into an almost infinite pool of information. As a result, a Hindu is now able to compare the advice of multiple Gurus from around the world on a singular issue. This is compared to mere hundreds of years ago, where there would only be one spiritual guide you would be able to access. This change prompts inquiry into how the role of the Guru has shifted in the digital age, and what the actual differences are between traditional and modern spiritual guides.

2.0 Traditional Spiritual Guidance

Guruship is as old as the Hindu religion itself. Traditionally, a Guru would live a simple married life and accept students to teach. Although there is scriptural guidance for the qualifications for good students, the ultimate decision lies with the Guru himself.

A student’s journey would begin by the new disciple offering a gift to his new teacher to show their gratitude for years of education to come. The student would then move into the household of the Guru, called a Gurukula in Sanskrit. This could either be the personal residence of the Guru, the temple where he resides, but most often a hut in the woods. At the Gurukula, the student would be taught basic Vedic principles and study sacred scriptures. Once a student’s teaching is complete, a Guru may ask his student for a Dakshina, a gift for teaching them. However, this does not repay the enormous debt the student has for his Guru, as he is obligated to spread his newfound knowledge to younger generations.

“When the teacher finds from signs that knowledge has not been grasped or has been wrongly grasped by the student, he should remove the causes of non-comprehension in the student. This includes the student's past and present knowledge, want of previous knowledge of what constitutes subjects of discrimination and rules of reasoning, behavior such as unrestrained conduct and speech, courting popularity, vanity of his parentage, [and] ethical flaws that are means contrary to those causes. The teacher must enjoin means in the student that are enjoined by the Śruti and Smrti, such as avoidance of anger, Yamas consisting of Ahimsa and others, also the rules of conduct that are not inconsistent with knowledge. [The teacher] should also thoroughly impress upon the student qualities like humility, which are the means to knowledge.”

— Adi Shankara (788-820),

Upadesha Sahasri 1.4-1.5

The life of Adi Shankara, an Indian Vedic Scholar and Teacher that championed the philosophy of Advaita Vedanta (a viewpoint which emphasizes the identity shared between Atman and Brahman), can help us better understand the life of a Guru. Shankara was born into a poor Brahman family and lost his father at an early age. With his mother as his teacher, he developed a brilliant mind, speaking fluent Sanskrit by the age of two and memorizing all four Vedas by age of four. By his twelfth birthday, he had left home to live an ascetic lifestyle. He then began searching for a Guru and landed up becoming a student of Govinda Bhagavatpada. There, Shankara further studied ancient Hindu scriptures such as the Vedas, Upanishads, Brahma Sutras, and more. At the age of thirty-two, he achieved Maha Samadhi, an experience in death where an enlightened one consciously releases themselves from the cycle of reincarnation. Before his death, he walked the Indian subcontinent spreading his knowledge as well as writing several books and commentaries.

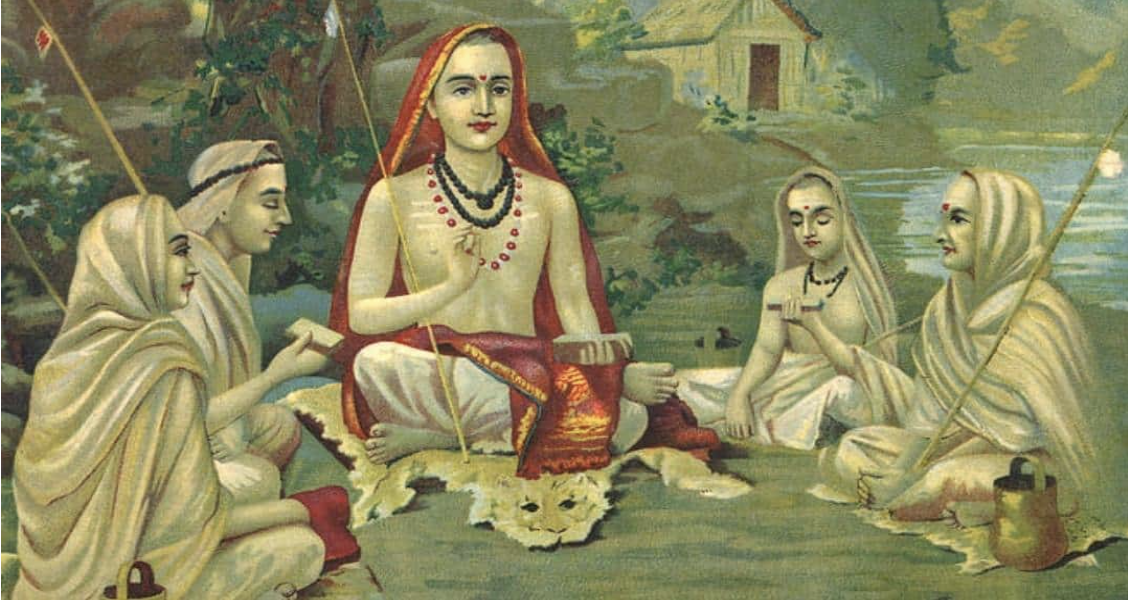

Adi Shankara (788-820) with Students

Now that the role of a traditional Guru is clear, it raises the question of why one would even seek out a Guru when ample scriptures are available. To answer this question, we go back to the notion previously mentioned that a Guru is comparable to a God, but rather teaches you in the flesh. In other words, a Guru can help a student focus on and work towards their own individualized Dharma, whereas a text gives all round advice. With that importance in mind, a Guru has the respect and full devotion of his students.

An extreme example of a student’s devotion for his Guru is exemplified in the story of Eklavya and Dronacharya present in the Mahabharata, one of the most important Hindu epics. The story begins long ago in Hastinapur (a city in northern India), where there lived a son of a local tribal chief named Eklavya. Wanting to learn archery from the renowned royal guru Dronacharya, Eklavya journeyed to his Gurukula in the nearby forest. When he arrived, Eklavya was disappointed to hear that Dronacharya could not accept him as a pupil because, according to state law, he could only teach royals. Eklavya, his desire to master archery still steadfast, took to the surrounding forest and sculpted a mud statue of Guru Drona, taking its blessing and practicing archery everyday. After a few years, Eklavya had become a master. One day while practicing, Eklavya was disturbed by a dog barking. In order to stay focused, he managed to shoot arrows into the dog’s mouth so the dog could not bark but was still unharmed. Coming across the dog later in the day, Guru Drona knew it was the work of a master archer and set out to find him. After finding Eklavya,Guru Drona became perplexed by his skill and asked the young man who taught him. Eklavya touched Dronacharya’s feet and said, “You, Sir. You are my guru. … I have been practicing archery religiously in front of your statue [after you said you could not teach me].” Dronacharya was shocked yet proud at the same time and knew this would put him in a difficult position as a royal teacher. As his Guru then, Drona asked Eklavya for his Dakshina, Eklavya’s right thumb, knowing that it would make it almost impossible for him to pursue archery in the future. Without hesitation, Eklavya cut it off and offered his thumb with gratitude. Touched by Eklavya’s dedication, Dronacharya blessed him to become the most gifted archer and to be a model of devotion. All in all, this story shows the faith that disciples have in their Gurus as well as a Guru’s ability to bless their students, even if a student is not taught face to face.

Traditional Gurus still exist in modern day. However, these spiritual guides often exist in rural settings where access to the internet is limited. Now, most often, Gurus as well as Hindu religious institutions have integrated modern online networks and technology to increase their audiences.

3.0 Modern Spiritual Guidance

As modern technology has expanded, so has the scale of Hindu mentorship. Because of the internet and electronic devices, hundreds of thousands of people can learn from a Guru’s lecture instead of a handful in his Gurukula. However, despite what may look different on the outside, at their core, a Guru’s primary goal has remained the same.

The notion that Gurus are still teachers, from the first centuries of the Hindu religion and continuing into the modern day, is essential in understanding the reason for how the way they operate has evolved. This is the view of the fact that a Guru’s purpose has remained the same: to impart knowledge that they deem necessary for their students. Moreover, for that reason, Gurus have to speak in a language that their disciples understand and appreciate.

This idea of shaping your language to your audience is significant because the audience of many Gurus has expanded and changed remarkably in the last century alone. If the same rhetoric used to teach back in the first century AD was used now, the idea of a Guru would be dead completely. Therefore, Gurus have to change their language to fit a modern audience, speaking with modern terminology and about issues that affect the current day populace. Moreover, as Hinduism spreads globally and expands throughout the world, the largest Gurus have to use a language and impart teachings that are universally applicable.

In addition to broadening their teachings, Gurus have also broadened their ventures. Instead of being a one man show in the woods, Gurus are now the leads of multi national charitable organizations with hundreds of staff members that promote Hindu religious teachings. In other words, from a macro scale, the biggest Gurus look more like brand marks of transnational organizations than spiritual guides.

In addition to resembling companies, Gurus have to sell themselves as a Fortune 500 Company has to sell their products. In ancient India, the journey to find another Guru would last weeks or even months, as most would have to walk or ride horses to their destination. In other words, local Gurus had limited competition, and were high in demand. This is starkly contrasted to the modern day, where a student can choose between thousands of Gurus who have lectured online. Therefore, in order to become successful and pull audiences, modern Gurus have to sell themselves to their audience and market themselves as unique and useful products: this could be through a philosophy, product, charisma or certain method. As Amanda Lucia would put it, “Contemporary global gurus are some of the most vibrant innovators in the field of Hindu religiosity” (Innovative Gurus: Tradition and Change in Contemporary Hinduism). In order to keep their followers, like an influencer, Gurus need to continuously innovate and bring new lessons to their followers.

The Mohan Ji Foundation and its founder Mohan Ji serves as a prime example of a contemporary Guru’s teachings and organization. Mohan initially led a happy life. However, after his daughter's death in 2000, he separated from his wife, his investments went sour, and he even lost his job. This prompted him to spend time in the remote spaces meditating the Himalayas, and in the wake of his return in 2003 he founded Ammucare Charitable Trust without any investments or compulsory payment. Ten years after his return from the mountains, he was finally able to find silence in the noise of life. Currently, he is head of Mohan Ji Foundation among other ventures teaching the philosophy that “spirituality is a lifestyle” (Mohan Ji Foundation). As part of the foundation, Mohan Ji charitable ventures include building places of worship across the globe, feeding those who cannot afford it, and planting fruit trees (that help the planet and feed people). Moreover, he travels around the world imparting knowledge on his followers across the globe. In 2024 alone, he traveled to Europe, Africa & North America.

Accept people (Don’t Judge)

Be positive

No agenda (Detachment)

Be Purposeful

Living insignificance (Selflessness)

Accept situations

Attitude of Service

Expect Nothing

No Binding [Agreements]

Feed the Hungry

The Ten Commandments of Being Mohanji

Unlike the deep scriptural study of the past, Guru Mohan Ji preaches implementing basic Hindu principles (as illustrated above) into daily life. His morning prayer includes gratefulness for another day and questioning what he can do for the world that day.

Mohan Ji lectures in English and teaches people across the globe. However, most of his followers hail from the western world. Therefore, through the focus on spirituality (a growing trend in the countries he is targeting) and using a more familiar language, Mohan Ji is able to capture his target audience. In addition to that, through unique teachings, charitable foundations, and a long history, he is able to advertise himself as a unique spiritual guide and trusted source of information. These ideas exemplify the previously mentioned ways of garnering an audience, because without them a Guru gets lost in the surrounding voices.

Mohan Ji at a New Fruit Tree Plantation

Although they might look like multinational conglomerates from an outside viewpoint, the foundations built by contemporary Gurus are far from that. They are charitable institutions deeply rooted in Hindu philosophy lead by Gurus speak on more generalized teachings of the religion. Essentially, as technology has grown and the world has become a smaller place, Gurus have adapted to take advantage of their new available resources and brought their teachings to a larger audience.

4.0 Comparison and Conclusion

Despite the change in how our societies operate and function, the role of the Guru in the Hindu religion has remained the same through the centuries: to teach. However, much has changed in the way Gurus guide their disciples, as the common language has changed and audiences have expanded tenfold.

Traditionally, Gurus teach their disciples in their homes, known as Gurukulas in Sanskrit. Moreover, they only teach a handful of students at a time, with full control on who to accept as disciples and how much to teach them. From there, students dive deep into Hindu philosophical teaching by reading scriptures, meditation, and other forms of lessons. Once their journey is complete, students have the obligation to spread the knowledge they’ve learned to others and create a good name for the Guru who taught them.

Conversely, because of the expansion of technology and decrease of time information takes to travel, Gurus no longer are constrained to teaching those in their homes. Through the utilization of the internet, Hindu spiritual guides have truly become global, and have started charitable organizations that have come to represent multinational corporations. Moreover, just like companies listed on the NASDAQ, Gurus have competition and have to advertise their spiritual services to students. This is in view of the fact that with the internet, students now can choose to follow an almost innumerable amount of Gurus from the comfort of their home. Therefore, Gurus have become the largest innovators in Hindu religiosity by trying to demonstrate their uniqueness to potential disciples. Now, they have to adapt their language and teachings to best fit their audience, as to grasp and keep their attention, especially in a world full of other distractions.

Nevertheless, contemporary Gurus are far from the companies they resemble. They run charitable organizations that encourage positive change instead of companies that only strive to extract more profit from their clients.

In essence, contemporary Gurus are just a continuation of the Gurus of the past. As technology has evolved, these spiritual guides have learned to take advantage of their new resources to help cultivate a larger audience and promote the religion globally.

5.0 Bibliography (APA)

References

Bikram. (2022, November 18). Adi Shankaracharya – The greatest teacher of Advaita Vedanta. VedicFeed. https://vedicfeed.com/adi-shankaracharya/

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2024, June 12). guru. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/guru-Hinduism

Das, S. (2019, March 8). The significance of the guru. Learn Religions.

Doniger, W. (2024, June 21). Veda. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Veda

Doniger, W. (2024, June 7). Purana. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Purana

Gold, A. G. , Basham, . Arthur Llewellyn , Buitenen, . J.A.B. van , Dimock, . Edward C. , Doniger, . Wendy , Smith, . Brian K. and Narayanan, . Vasudha (2024, June 19). Hinduism. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Hinduism

Hinduism - origins, facts & beliefs. (2023, November 16). History. https://www.history.com/topics/religion/hinduism

Kamath, R. (n.d.). The ten commandments of being Mohanji. Mohanji. https://mohanjichronicles.com/mohanji-blog/the-ten-commandments-of-being-mohanji/#:~:text=Mohanji%20has%20zero%20expectations%20from,doership

Lucia, A. (2014). Innovative Gurus: Tradition and Change in Contemporary Hinduism. International Journal of Hindu Studies, 18(2), 221–263. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24713672

M, B. (2013, January 16). The Vedas (Rig-veda). World History Encyclopedia. https://www.worldhistory.org/image/1027/the-vedas-rig-veda/

Mahasamadhi. (2023, December 21). Yogapedia. https://www.yogapedia.com/definition/5825/mahasamadhi

Menon, S. (n.d.). Advaita Vedanta. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://iep.utm.edu/advaita-vedanta/

The nature of God and existence in Hinduism. (n.d.). BBC. https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/zmtj2nb/revision/1#:~:text=The%20nature%20of%20God%20and%20existence%20in%20HinduismBrahman,deities%20%2D%20presentations%20of%20the%20divine

Ruchika. (2022, September 12). The story of Eklavya and Dronacharya for kids. First Cry. https://www.firstcry.com/intelli/articles/the-story-of-eklavya-and-dronacharya-for-kids/#:~:text=I%20give%20you%3F-,%27,teaching%20me%20all%20this%20while

Temple Purohit. (2015, July 27). The guru shishya parampara. Temple Purohit.

Who is Mohanji. (n.d.). Mohanji. https://mohanji.org/who-is-mohanji/